Following on from computing eras but before getting to my “Thinking About AI” series, there’s one intersection I’d like to bring up which is the notion of “people’s computing.” This idea of people being front-and-center of computation, and thus technology, once held sway but has often been in danger from a wider technocracy.

I mentioned in the previous post that I’ve done a lot of research into gaming history, particularly around the distinctions of ludology and narratology. As I embarked on a lot of that research, I found an interesting starting point around where computing and education intersected.

This intersection provided a very fertile ground for the development of computer games and also artificial intelligence, the latter of which was often used with and against the former to determine its viability and actuality.

What’s interesting is that while gaming saw a great deal of experimentation because it became democratized — due to the democratization of computing — there was less of this with artificial intelligence. The latter was not as democratized and thus the experimentation was confined to researchers or academics.

Thus people, in the broad sense, were front-and-center with gaming-as-computation and very much in the background with AI-as-computation. But let’s dig into a little history here and look at how humans and technology intersected at some pivotal moments.

A Historical Pivot Point

A very key moment in the microelectronic revolution, which eventually led to computing becoming accessible to many people, was the launch of the Sputnik satellite on 4 October 1957 by the Soviet Union.

In the United States, the launch of Sputnik provided the impetus for administrators and educators to reconsider American education as a whole.

It was felt a “space race” was coming — in fact, a technology race — and thus American education had to prepare its youth for that. Better schooling was required, particularly around math and science.

Computing in Education

In September 1958, the United States Congress passed the National Defense Education Act.

Not exactly riveting reading, I can assure you, but it provided funds to improve teaching, with an emphasis on teaching science and mathematics. The federal government thus made money available for “innovative approaches” to education. A primary focus of innovation in this context was using technology in the classroom.

Money supplied by the government, as well as private institutions like the Carnegie and Ford Foundations, made it possible during the early 1960s for schools to experiment with new and innovative educational methods around technology.

This impetus for adding technology into schools, not surprisingly, had a direct impact on the history of computing.

A Mythology Formed

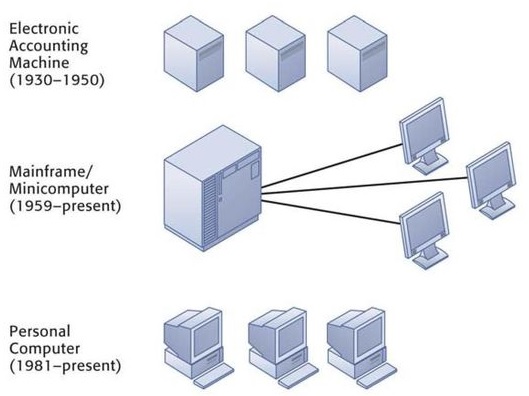

If you investigate this history, you generally encounter a persistent mythology in computing. That mythology is that computing went directly from a type of priesthood or elite model of mainframe computing to the liberation from this by the so-called “homebrew hobbyists.”

These hobbyists were non-professionals who “worked out of their garage” — hence the “homebrew” — and ultimately gave us personal computers, one entry point being the kit-based Altair in 1975 to the 1977 “trinity” of the Commodore PET, Apple II and TRS-80.

In fact, usually the Commodore and TRS-80 are left out of the mythology and it’s seemingly assumed that Apple was solely responsible for carrying the world into a new golden age.

All of this eventually led into the early 1980s with the IBM PC and its various clones. Those developments ultimately led to diversification in the 1990s as the “World Wide Web” became the face of the existing Internet.

So the general form of the mythology is that we had corporate/institutional computing and we had personal computing. And the shift between them was dramatic and instituted by relatively few people. And these were “special” people who became “big names” such Bill Gates and Steve Jobs.

Yet in between those institutional and personal computing contexts, we had what we might want to call “people’s computing.” This is a part of the history — and I would argue a very large part of it — that often gets entirely dismissed, assuming it’s even known about at all.

This is the crucible era that I referred to in the previous post. There was a decade, from 1965 to 1975, where students, educators, and enthusiasts — ordinary people and not “big names” — created personal and social computing before personal computers or the broadly public and accessible Internet became available. At that time, the newly emerging people-focused computing access moved in lockstep with network access via time-shared systems.

And those time-shared systems saw their most vibrant use in the context of educational institutions.

Thus this technology context combined with the education context meant that primary (K-12) schools and high schools, as well as colleges and universities, became sites of technological innovation during the 1960s and 1970s.

Students and educators were the ones who built and used academic computing networks, which were, at this time, facilitated by that new type of computing called time-sharing.

Time-sharing was a form of networked computing that relied on computing terminals connected to some central computer via telephone lines. Those terminals were located in the supremely social settings of middle school classrooms, college dorm rooms, and university computing labs.

Acting as communal institutions, these schools and universities enabled access to and participation with these systems. And this was supported by eager state governments as well as the National Science Foundation.

If you’re interested in details about this history I highly recommend John Markoff’s What the Dormouse Said: How the Sixties Counterculture Shaped the Personal Computer Industry. Also worth reading is Joy Lisi Rankin’s A People’s History of Computing in the United States and Bob Johnstone’s Never Mind the Laptops: Kids, Computers, and the Transformation of Learning.

Shared Working and Shared Work

Collective access to a social, communal resource meant the possibility of storage on a central computer that all the terminals connected into. This meant that users could share useful and enjoyable programs across the network.

The “enjoyable” part was often provided by the use of simulations and games. These were obviously of a lot of interest to young students, regardless of their age or skill level. And these simulations and games, more than anything else, led to a democratization in computing.

Keep in mind that, by design, time-sharing networks accommodated multiple users. Multiple users meant more possibilities for cooperation, community and communication. This in turn allowed for a great deal of experimentation, collaboration, innovation, and inspiration.

A key focus there is on experimentation. The democratization of computing is what led to that experimentation.

Advocates of 1960s and 1970s time-sharing networks often shared the belief that computing, information, and knowledge were becoming increasingly crucial to American economic and social success. That viewpoint was related to another, more all-encompassing viewpoint which was that computing would be essential to what many perceived as an emerging “knowledge society.”

This idea was considered a bit in Time Magazine from April 1965.

Such a society would certainly be predicated on the sharing of knowledge and thus computing would have to be an essential part not just of storing that knowledge but also making sure it was appropriately democratized. Fostering those viewpoints, and those practices, was certainly another way that the technology and education contexts were aligning because it was perceived that the upcoming generation would be the one to capitalize on these grand visions.

Worth noting that artificial intelligence was not really part of this overall focus at all. It’s not that it wasn’t known about necessarily; but rather its application and use to a wider public was barely considered. A good book that traces a lot of thought on the subject via numerous essays is AI Narratives: A History of Imaginative Thinking about Intelligent Machines.

It was in this historical context that people began discussing the possibility of a national computing network. This would be a network that was comparable to the national telephone network or the national electrical grid.

Computing as Commodity

During the 1960s, those focused on academics and those focused on business both grew increasingly interested in — and evangelical about — this idea of a national computing utility. Perhaps even multiple such computing utilities. The idea here was that computing services would be delivered across the United States over time-sharing networks.

Entire businesses were launched to realize this particular vision. That vision was a world in which all Americans benefited from computing access in their homes and workplaces, just as Americans benefited from the comparable national utilities of water, electricity, and telephone service.

Technology had to enable all of these grand visions, of course, and, for a time, there was a symbiotic relationship with the minicomputer marketplace, which provided a lower cost alternative to very expensive and very large mainframes. Those were mainframes that the schools often couldn’t afford.

It was minicomputers that the terminals at various schools were connecting into with their various access methods, such as teletype terminals.

Minicomputer manufacturers, like the Digital Equipment Corporation and Hewlett Packard, monetized their support of educational materials to sell their machines, further aligning the technological with educational interests.

A Computing Ecosystem Formed

What I hope you can see is that the histories of educational institutions and the technology companies are woven together but still distinct. They certainly had areas where their interests aligned but also, of course, had very specific interests of their own that they worked toward.

It was the educational aspects, however, that would give rise to the idea of people’s computing, with the technology companies figuring out not only how to be enablers of that but how to make as much money as they could doing so.

The early, more localized networks collectively embodied the desire for computer resource sharing. In an education context, this immediately situated itself around a community of interested individuals joined by computing networks. The desire was for a form of communal computing which could be extended beyond the education context.

That “beyond the education context” impetus is what propelled the push for the national computing utility that I mentioned earlier and the promise of a nation of computing citizens. This further allowed for the idea of computing being brought into the home and thus becoming more “personal.”

A Broad Focus for Computing

So let’s consider the broad sweep of the history being discussed here as it developed.

We ended up with educational computing enthusiasts like Noble Gividen, Bob Albrecht and David Ahl who did a massive amount of work around introducing computing to young students. Various computing projects within education started, such as Project SOLO, Project LOCAL and the Huntington Project.

Those projects allowed for the work or the enthusiasts, and their students, to be shared in various newsletters and periodicals.

There were also education initiatives such as the Board of Cooperative Educational Services (BOCES), Total Information for Educational Systems (TIES) and the Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium (MECC).

For those who know their gaming history, BOCES is what led to The Sumerian Game which ultimately provided the basis for all Hammurabi variants. TIES and MECC are the contexts in which The Oregon Trail proliferated.

As all of this democratization and experimentation occurred, there were people who began to build hobbies around the new technology and, eventually, there were people who began to build careers around the new technology.

All of this forged a crucial link between the computer — and thus computing — and its larger social and economic environment. This, in turn, led to different technical communities and distinctive subcultures and thus varying ecosystems. And that, in turn, led to discussions about the relationship between science and craft in engineering practice, both of hardware and software.

Those communities, subcultures and discussions eventually led to hardware being a consumer technology and to software being a commercial industry.

We thus eventually saw the rise of an information economy serving as the backbone of an information society. Time Magazine, in its February 1978 issue, certainly recognized that.

But notice how the focus shifted. We were apparently a “computer society” versus the “knowledge society” that was originally envisioned. The technocracy had already started to shift the dynamic.

In this “computer society,” games and gaming have proved to be a staggering multi-billion dollar industry, one that, at the time of writing this, easily outpaces all other forms of entertainment. And, to be sure, there were various forays into artificial intelligence, most of which led to so-called “AI winters.”

Yet here we are now, as I write this, seeing yet another major foray into artificial intelligence and its broad dissemination across an array of industries. That means we are seeing a lot more experimentation and thus the possible democratization I mentioned previously.

The Historical Broad Stroke

So here’s where my initial historical forays led me: in the late 1950s, computers were, for the most part, remote, inaccessible, and unfamiliar to pretty much everyone.

Speaking just to the United States, there were approximately six thousand computer installations and those tended to cluster in military, business, and research-focused university settings. Computing was focused on the academic, industrial, and military. Individual access to computing was extremely rare.

As per the broad history I recounted above, computers would start to spread from military and university installations through factories and offices and, eventually, into the home.

But all that took a little bit of time. And in between that time — between, that is, institutional/corporate computing and personal computing — there was a fascinating emergence of people’s computing. And a whole lot of that people’s computing was driven by a focus on simulation and games and, to a lesser extent, artificial intelligence.

Moving Towards People … Again

I said earlier that for a time “computers were, for the most part, remote, inaccessible, and unfamiliar to pretty much everyone.” Well, that’s what a lot of technology is like for many people even today.

We can’t let the fact that we walk around with phones and tablets that are essentially computers blind us to the fact that how things actually work and why they work they way they do is opaque to many people. those who work in the testing specialty in particular are very well aware of the broad opacity that exists between people and the technology they regularly consume.

If that’s the case even for casual applications that we use on our computers or mobile devices, imagine how much more so it is for artificial intelligence and machine learning.

We were in the institutional phase of the computing with this technology. Now we’re getting into the corporate phase of the computing. A goal is to get to the personal computing phase of all this and to do so as rapidly as possible, given the possible disruptive nature of the technology.

But to do that, we need that bridging element once again: people’s computing.

A key focus I mentioned earlier was on experimentation. The democratization of computing is what led to that experimentation. And continued experimentation led to further democratization. A very effective feedback loop!

We’re starting to see more of the democratization of artificial intelligence in ways that the general public is more able to consume and thus experiment with. But what are we going to do with it?

Those students and educators who did that initial experimenting in that crucial “crucible era” of 1965 to 1975 were, in effect, acting as testers. They were putting pressure on an entire arena of design thinking as it pertained to computation. Sure, no one was necessarily aware of that nor would they have likely articulated it that way. But that is what was happening.

We need the same thing now.

Testing Keeps Us Honest About Tech

Experimentation and testing is what’s going to allow the new emerging technologies to have a chance of succeeding in a way that doesn’t neglect human needs and values.

My next series of posts on “Thinking About AI” will be my small contribution to building the world I most want to see humans living in: one where we are in suitable awe of the technologies we are able to create but where that awe does not blind us into losing what is distinctly human simply because we have created and adopted technologies that, in some ways, can surpass us. In short, we have to be able to understand how this technology actually works so that we can better put it to the test.

Brian Greene, in his book Until the End of Time: Mind, Matter, and Our Search for Meaning in an Evolving Universe, framed what I think so very well, such that I’ll quote it at length:

We emerge from laws that, as far as we can tell, are timeless, and yet we exist for the briefest moment of time. We are guided by laws that operate without concern for destination, and yet we constantly ask ourselves where we are headed. We are shaped by laws that seem not to require an underlying rationale, and yet we persistently seek meaning and purpose. We have punctuated our moment with astonishing feats of insight, creativity, and ingenuity as each generation has built on the achievements of those who have gone before, seeking clarity on how it all came to be, pursuing coherence in where it is all going, and longing for an answer to why it all matters.

Obtaining substantial knowledge typically comes from disciplined and voluntary mental dedication over an extended duration. This is often fueled by sheer perseverance and rigorous effort. As a consequence of this pedigree, my firm conviction is that this becomes not only an intellectual pursuit but also a moral and ethical endeavor. It is, in line with my previous post, a large part of the “meaning” of life.

It’s my strong belief and conviction that this endeavor, particularly when a technocracy is present, must be focused on the desire to search for truth, to think critically, to communicate effectively and to serve wisely and compassionately in support of human dignity and the common good.