There’s an interesting cultural effect happening within the broader testing community. I’ve written about this before, where my thesis, if such it can be called, has been that a broad swath of testers are using ill-formed arguments and counter-productive narratives in an attempt to shift the thinking of an industry that they perceive devalues testers above all else. This has led to a needlessly combative approach to many discussions. In this post I want to approach this through a couple of parallel lenses: that of game studies, linguistics, and anthropology. That will lead us to insider (emic) and outsider (etic) polarities. It’s those polarities that I believe many testers are not adequately shifting between.

A couple of prefatory remarks here. Firstly, I’ve talked about the broad concept of shifting polarities before so what I say here is hopefully in line with that. Secondly, as with all such heavily opinionated posts, it never hurts to start with saying that I entirely realize that all this is, in fact, opinion. I believe I have a good basis in empirical fact for forming these opinions. But, nevertheless, opinions these remain.

The “Camps” Around “Culture Wars”

Before digging in, I want to preface this even further with an interesting bit I read from the book Seeking God in Science: An Atheist Defends Intelligent Design by Bradley Monton. The author mentions that “the battle over intelligent design is like a war between two camps.” I somewhat see this in testing, as well, with testers either in a “war” with developers (or development managers or decision makers of various kinds) or at “war” with each other.

Please note the quoted “war” as the goal isn’t to be melodramatic here. But I would ask you to keep in mind that idea of “war between two camps” for a moment. In his book, Monton recounts the words of an intelligent design opponent who was given a draft of the book for review:

Unfortunately in this debate a position between two sides, which you seem to adopt, is hardly tenable. It is a cultural war whose outcome will have immense consequences, so a book, to be useful, must unequivocally take a side and defend it vigorously. A position of supposed impartiality (which is hardly possible) necessarily serves one side despite the author’s intention to remain unbiased.

Notice the “cultural war” reference there? Any time people feel they are in a “cultural war,” that tends to harden the defensive lines and augment the offense against anything perceived to be threatening to the culture.

As Monton states in response to that critique:

I think part of the truth is that it’s overly simplistic to think that there are just two sides to the intelligent design debate; there are many different positions that one can take, and I’m taking one position out of the many.

Exactly so. Being able to look at many different positions — at varying contexts that may lead to a way of thinking and terminology used in that way of thinking — is pretty crucial. But it requires not hardening into camps of binary interpretation.

So this “cultural war” reference and the idea of taking sides in “camps” plays out in the context I mentioned above regarding testing. I often feel like a growing segment of testers are being taught that they’re in a culture war and they are thus reacting against threats to the culture. My opinion is that this reactive nature is actually causing a wider industry to not listen to such testers at all, thus compromising their mission from the start. And to the extent that this spreads wider, the impact on specialist testing in the technology industry as a whole is potentially quite dramatic.

A short version of this whole narrative I’m going to share with you in this post: I agree with many testers that the testing specialty is potentially in danger in our industry. Where I disagree is that I feel this danger is, in many cases, self-inflicted and is due in large part to how a growing vocal segment of the testing community is framing its messages to the wider industry.

The Rise of Dichotomies

The first context I’ll draw a parallel with here is that of various digital humanities scholars approaching video games from the perspective of story (narratologists) or of play (ludologists). I’ve actually started talking about these ideas in a new blog with my post “Starting a Ludic History.” If curious, and if you want a source besides myself in this post, you can see this played out in books like The Composition of Video Games: Narrative, Aesthetics, Rhetoric and Play, The Play Versus Story Divide in Game Studies and Storytelling in Video Games: The Art of the Digital Narrative.

- For the ludologists, the position they take is that digital games are an entirely new medium. The relationship between a player and the games they play represents a new form of human activity. As such, the ludologists believe that there really are no antecedents to this and scholars should concentrate on game mechanics and the game/human interface above all else.

- For the narratologists, the position they take is that digital games are really just one more evolutionary step in storytelling that extends back to the start of our species. The antecedents here have been systematized in the notions of drama all the way back to Aristotle and all the way up to current novelists, screenwriters and filmmakers.

So, somewhat simplistically, the ludic approach advocates a split of game studies away from previous forms of storytelling while the narrative approach sees a new format of previously existing forms of storytelling. What I really want you to take from this is that we have not just an ontological position being staked out but an epistemological position as well. I covered this a bit in my post on “The Theseus of Testing” and in my ideas around the basis of testing.

In this game studies context, you can probably see the “camps” that formed here and you can probably imagine that some participants on both sides felt a “cultural war” was being waged around the true ambit of gaming or narrative, depending on whatever position they hitched their conceptual wagons to. In fact, Henry Jenkins, in his article “Game Design as Narrative Architecture”, from March 2009, said:

A blood feud [has] threatened to erupt between self-proclaimed Ludologists, who wanted to see the focus shift onto the mechanics of game play, and the Narratologists, who were interested in studying games alongside other storytelling media.

Note the idea of a “blood feud”, keeping in line with the theme of opposing camps or viewpoints. Related to this overall context, I really like something that Jesper Juul said:

Video game studies have so far been a jumble of disagreements and discussions with no clear outcomes, but this need not be a problem. The discussions have often taken the form of simple dichotomies, and though they are unresolved, they remain focal points in the study of games. The most important conflicts here are games versus players, rules versus fiction, games versus stories, games versus broader culture, and game ontology versus game aesthetics.

That’s from his book Half-Real: Video Games Between Real Rules and Fictional Worlds. Why is that relevant? It’s the focus on dichotomies that interested me and, unlike Juul, I do see some problems there. Hardened dichotomies often come up in so-called “culture wars” where we have different “camps” of people. Certainly we’ve seen how well that works out historically; even recent history offers many examples for us to ponder.

This doesn’t mean what’s being fought over is wrong. What’s being fought over can be very justified. But we can’t overlook the fact that it’s being fought over. And often by sides that are talking past each other, not with each other. Insiders and outsiders on both sides and who is considered which is, of course, relative.

So consider that just within testing itself we have these dichotomies as well: “tests versus checks”, “write tests versus perform tests”, “automated testing versus manual testing” and so on. These are the weaponized phrases that testers are often using to combat the perceived threat to the testing culture. These dichotomies lead to a potential insider/outsider misalignment that, when persisted, leads to grievous schisms within a discipline but also conceptual chasms to other intersecting disciplines. That “insider/outsider” bit is going to explain the title of this post, so stick with me here.

Talking Amongst the Insiders

One thing I’ve argued is that testers are great at talking to themselves, repeating points to each other that they already agree with. They are much less good at talking to non-testers, at least in my experience. My evidence for that: discussions on various social media platforms. Further evidence: history. Specifically, history within the technology industry. Yet further evidence: the correlation between the rise in stridency of certain tester arguments, particularly since roughly 2009, coupled with a decrease in interest in testing as a specialty but not a decrease in testing as a practice. By that latter point what I mean is, I’ve certainly seen continued interest in testing as a practice in the industry. But often it’s focused more on how developers can do the testing. Or how tooling can do the testing. But I’ve seen less interest in testing as a specialty practiced by skilled practitioners.

Let’s step back to the game studies part for a second.

- From the narratologist standpoint, they are generally hoping that the practitioners and evangelizers of the ludic approach — designed as it is to support claims of a complete departure of digital games from previous narrative media — will at least attempt to learn from previous debates that followed a very similar pattern, where something was claimed to be entirely new.

- From the ludologist standpoint, the same hope exists except in the other direction. They hope that narratologists will learn from past debates where something was assumed to be just one more thing in a long line of pre-existing things when, in fact, it was something entirely new that only had superficial resemblance to what came before.

This is something I’ve long asked testers to do: learn from what has and has not worked in the past, in terms of “debates” or “discussions” around how testing is framed in the wider industry. I did this most recently in my automation history post as well as in my call for a new narrative.

From the game studies example, what’s important to understand from the context here is that the narrative approaches had much more resonance to “outsiders” to the game studies discipline. The narrative approach was something familiar that they could understand and relate to and thus engage with. Ludic approaches didn’t have that same effect and, in fact, often turned away many outsiders.

And when I say “turned away” it wasn’t because of some simplistic reason such as “Those outsiders are just unwilling to engage with the nuances.” No, instead, it was largely because ludic evangelizers always seemed to be framing dichotomies and telling everyone that everything they knew was wrong. But if and when the narrative approach was used as a hook, then the ludic approaches could more easily be communicated and potentially more readily received.

The problem was that insiders to the discipline were really attaching themselves to the ludic side of the dichotomy, even when it was clear that not only did these conceptions not frame themselves well with the outsiders, but the arguments often seemed either delusional or simply irrelevant to those outsiders. You would see things like: “Oh, that stuff you see in the game that seems to tell a story around certain characters in a setting with events happening relevant to a guiding plot? Yeah, that’s not narrative. In fact, calling that narrative is wrong. You’re silly for doing so.”

Key takeaway here: a “ludic approach” achieved popularity among scholars of digital games (insiders) but a “narrative approach” translated outside the discipline better. It’s definitely interesting to learn about why that is but that’s not going to be my focus since, ultimately, my focus here isn’t game studies. The “insider/outsider” aspect is a part of my focus.

So keep in mind what we potentially have: established “camps” that have framed “dichotomies” and those dichotomies led to various insider and outsider perceptions, where the insiders often felt threatened by the outsiders and thus a “culture war” was necessary. (Maybe even a “blood feud” here and there.)

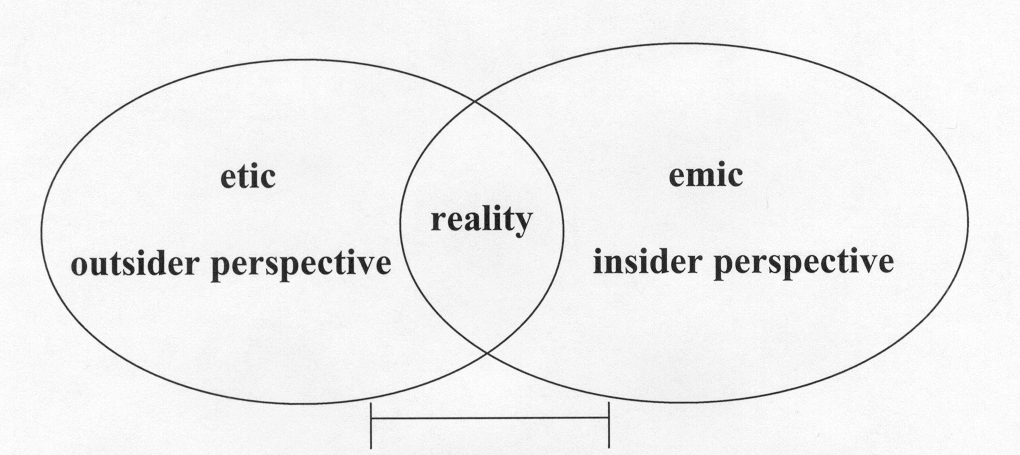

Emic versus Etic

Okay, let’s finally get to the terms that are in the title of this post. The context here is that, in the mid 1950s, a linguist at the University of Michigan named Kenneth Pike came up with a new kind of terminology in an attempt to understand the relationship between the languages he studied and the cultures that actually used those languages.

For Pike the problem he found was that non-native speakers (listeners) of a foreign language often could not determine sound variations that, to native speakers, carried cultural meaning. Pike decided to use the terms “etic” and “emic” around language units. So there were units of cultural expression that were obvious to an outsider (etic) and units understood only from within the culture (emic). Incidentally, Pike derived these terms from phonetics, which refer to the sounds of a language, and phonemics, which refer to the meanings of those sounds. If you want to read up on Pike’s thoughts, I recommend his Language in Relation to a Unified Theory of the Structure of Human Behavior. Make sure to get the second edition, published in 1967.

In doing all this, Pike hoped to do what game studies scholars do and presumably what testing scholars do: find patterns of meaning. Consider that a ludologist might look for translatable similarities between games or the actions taken within games. A narratologist might look for equally similar translatable narrative structures, such as characters, settings and events. Both groups are attempting to do what Pike was also attempting to do around patterns, of which he said:

No pattern can occur in isolation, autonomous from a larger kind of context or set of assumptions, and still be meaningful to human beings. Patterns require larger contexts, with relevance to more inclusive patterns, if they are themselves to be meaningful to us. The total autonomy of parts of knowledge does not exist.

That quote is from Pike’s Talk, Thought, and Thing: The Emic Road Toward Conscious Knowledge from 1993. I didn’t have these ideas in mind when I wrote my “Testing Is Like …” post but it’s certainly part of what I was articulating there. Patterns of thought that I saw in testing, I saw reflected in many other disciplines. Thus was the pattern in testing situated within a larger context.

In Pike’s conception, the emic perspective became the insider’s perspective, and could only be understood by direct action on the part of the user of a language. In contrast, the etic perspective was the outsider’s perspective. Crucially, it was Pike’s contention that both perspectives were inherently necessary for efficient social science and effective understanding.

So, in the game studies context, consider Pike’s contention in relation to the idea that both ludic and narrative approaches might be fully required in order to truly come up with an understanding of how to craft experiences with digital games. However — and this is a crucial point — to achieve that requires talking with the outsiders in a way they’ll understand and respond to but also in a way that the insiders don’t feel compromises what they very much believe.

Applied To Testing

Consider how this might tie into testing discussions that you see in our industry. Testers routinely say things like “developers just don’t get it” or “development managers just don’t get it” or “those making hiring decisions just don’t get it” and so on. You’ll notice these testers rarely, if ever, question if perhaps they are simply not framing an insider message in a way that an outsider can respond to. It’s generally the case that it’s always about somebody else “not getting it.”

That right there has been one of my sticking points with many of my fellow specialist testers: being able to craft an insider (emic) message in way that an outsider (etic) reception can be encouraged and facilitated. Note that this requires understanding that sometimes the outsiders might have a better framing. The goal here should be making sure that any such framing, regardless of directional orientation, is operationally useful in terms of making sure testing, as a specialty by skilled practitioners, is valued within the industry and not seen as just some sophist discipline practiced by fractious groups of people whose only interest is in telling you how every word you use is being used in the wrong way and how everything you think is probably totally inaccurate.

You know what that sounds like, right? It’s sounds like a conspiracist thinker. “Everything you think you know is wrong! Even the way you speak is wrong! But I have the right words that will lift the veil from your eyes. I have the right way to think about things such that you are no longer deluded and duped by the Industry.” And if you don’t think many testers sound exactly that way to many outsiders to the discipline, then you probably aren’t paying attention or not talking to enough honest outsiders.

In not having a good and solid way to frame the insider view to the outsider view, as well as a lack of framing the empirical evidence for why certain distinctions make sense to promote, I believe the utility of testing — again as a specialty practiced by skilled practitioners — is at risk. I would say the risk is certain in the larger context of the industry and perhaps technology culture in general. This was also happening in game studies, by the way, although the discipline seems to be course correcting a bit in recent years.

I also do think testing can become at risk even amongst testers themselves because I do believe there is an ethical mandate to being a mistake specialist. Part of that ethical mandate is to allow an insider framing to be situated to an outsider but also to allow outsider view to inform the insider views. We need people to care about this stuff as much as we do and if we compromise our ability to do that, I do believe we have a bit of an ethical dilemma. Note: ethical dilemma, not moral dilemma. Again, I don’t want to go for melodrama here.

Pike wanted to have these insider/outsider discussions in a way that was actually useful. The problem was that, as he (accurately) perceived it, these discussions only happened intermittently and transiently and then, largely, faded away. While Pike’s ideas were adopted in both linguistics, and eventually anthropology, they were really only discussed in any substance for about three decades. That may sound like a long time but it’s worth noting that those discussions were had with a visibly increasing lack of substance and a visibly decreasing interest.

I certainly have seen something similar in the testing industry, where ideas, at least from testers, have started to lack operational substance — although perhaps gaining some sort of philosophical substance — and thus there has been decreasing interest from a wider industry. One example of that in action is how developers have been most often front-and-center in what are considered, by hiring managers and decision makers, to be useful testing innovations and experiments.

Comprehension and Relevance

So what happened with Pike’s terms? Well, as I said, they were used in anthropology and it was actually there, as opposed to linguistics, that the terms had their greatest influence. That being said, it’s worth noting that they were almost universally misunderstood, at least in terms of Pike’s original meaning. In anthropology the terms emic and etic were eventually dispensed with in favor of, simply, calling these the “insider’s” and “outsider’s” view. Okay, but why is that a problem? Isn’t that what they were? Yes, but, as Pike noted, there was a tendency to assume a dichotomy between the emic and etic when framed in this way when, in fact, in his own words, they “do not constitute a rigid dichotomy of bits of data, but often present the same data from two points of view.”

So in the game studies context, for example, to understand a ludic view of a game you have to play it. You need to be what’s called a “participant-observer” in anthropological terms. However, to take a wider view, it’s sometimes easier to look for larger — narrative-based — cues that can be examined from game to game as a “nonparticipant-observer.” Yet, in both cases, the object of study remains constant and it’s only the perspective of the observer that has changed.

This is the same idea as being able to perceive work at critical distance. The idea here is the ability to change perspectives, to have an intuition for abstraction as I’ve talked about it before, from one mindset (actually doing something) to another mindset (think about what it means to do that something).

I’ve found modern testers are often not being encouraged to look at the perspective of the observer being changed. Thus do we get the fundamentalists and the orthodoxy. So here we might equate the developer, or development manager or product manager, with a “nonparticipant observer.” Culturally speaking, it’s worth noting that this gets really tricky in our industry because developers are called upon to act as testers in limited contexts. So developers move between “participant-observer” and “nonparticipant-observer” modes. Testers have to do likewise, such as when they engage with automation.

Pike, later in his career, offered a specific view.

[An] emic unit, in my view, is a physical or mental item or system treated by insiders as relevant to their system of behavior and as the same emic unit in spite of etic variability.

That comes from his essay “The Emics and Etics of Pike and Harris” published in Emics and Etics: The Insider/Outsider Debate in 1990. (The “Harris” there refers to Marvin Harris who debated Pike quite a bit on these ideas.) Regarding this particular idea, Matthew Kapell, who also looks at the work of Pike in the context of digital games, says the following in The Play Versus Story Divide in Game Studies:

The classic example of what Pike meant comes from Chinese, but the American example may be somewhat more fruitful here. Where a person from Oregon might say “gah-rahge” to express the structure they park their car in, a person from Boston might pronounce the same word as “gare-ege.” But all speakers of American English hear the same emic category while an external listener may have trouble in realizing they are hearing the same word pronounced in two different dialects.

So testers have to realize that while they try to make a distinction between, say, a “test” and a “check” — and let’s call that an insider view — many others will simply hear the same idea being spoken of but with a different word. So we have a bit of an inversion from the above example: we have an etic perception of one term “test” being called two things (“test” and check”) while the emic perception is that these are two entirely different things. What gets compromised is “translation to the outside.” In Pike’s words, he would say etic comprehension is compromised.

Outsider people may — and do, I assure you — wonder why we have to use some existing word (“check”) and set it up in opposition to “test” and then claim that this is somehow meaningful. It may be meaningful! But you can’t just expect outsiders to take your word for it. And even if they take your word for it, what change in mindset or behavior actually occurs as a result of making this change? Because it’s that latter question that people are really going to be concerned with.

So it’s not just comprehension here between insider/outsider. It’s also demonstrable relevance. This has a nice corollary in how we frame this for children as they learn to consume stories.

In this same context, you’ll hear testers say “you don’t write a test, you perform a test.” And what they singularly fail to anticipate is the outsider who says, at minimum, “Why can’t I do both?” And who probably also says: “How is helping us get things done in a better way?” This occurs similarly with a newer bit of tester-speak I’ve heard more and more recently, which is saying “I’ve shown you something can work but not that it will work.”

Imagine you’re getting, say, your car fixed because of faulty brakes. And your mechanic said something like that to you. “Well, I’ve seen that the new brakes I’ve installed can work, but I’m not saying they will.” There may be some overall philosophical logic to this statement of course — that there are no certainties in life — but most intelligent people know that and so they don’t want that philosophy thrown at them when they’re looking for something a bit more empirical.

So outsider comprehension isn’t the only goal. The goal is also, presumably, to have the outsider (etic) perspective come to align with the insider (emic) perspective, at least insofar as perceived relevance.

That has largely failed to happen in the testing context within the technology industry. Many testers will argue that this is because of testers — like me, perhaps! — who won’t toe the line and join in promoting the categories and also because other “outsiders” just aren’t interested in listening. My contention is different: I feel that people don’t listen because the terms, and the rationale behind them, just don’t resonate.

The wider industry I keep mentioning, admittedly, tends to be a technocracy and it values economies of scale when it comes to various decisions, including how best to test that something works. This inevitably leads to a recipe of assuming automation is the appropriate way to handle many situations. Testers saying “But that tool only checks, doesn’t test” is an emic perspective. It has very little (perceived) etic utility. The same applies when testers move that abstraction a bit and say “you don’t write a test, you perform a test.” Likewise, many testers fight against the term “manual testing” — and for good reasons in a lot of cases — but often predicated upon the idea that somehow those they are trying to convince don’t understand that the term “manual testing” means “human testing.” But those people often do get that. What they doubt is the “human testing” has enough economy of scale.

And that doubt is the discussion to be having with people who may value testing but who currently feel testing would provide scalable value if automated. Telling them tools “check” but don’t “test” doesn’t really do much. That can seem meaningless to outsiders, at best, or obstructionist, at worst.

I’m picking on just a few of the dichotomies that testers have promoted and I don’t want to risk a caricature of the views. It’s very possible for many testers to expand on the “test / check” distinction. The challenge is I rarely see them doing so in a way that sways outsiders. It’s very possible for testers to back up the “can work but not necessarily will work” with examples of the testing they’ve done to surface potential risks but, if you can do the latter, you don’t really need the former phrasing at all.

I also want to point out Michael Bolton’s Alternatives to “Manual Testing”: Experiential, Interactive, Exploratory article which, in my view, provides a very reasoned and reasonable way to frame testing for outsiders. Even with those distinctions, you have to be prepared for outsiders who actually see more complication to testing by introducing more words because many of them are dealing with testers who they just heard rattling off some of the phrases I’ve mentioned.

Framing For the Outsider

Again I want to note a core historical fact here: the emic and etic categories first offered by Pike were useful ways to examine other languages and cultures. Yet when adopted by certain scholars, these concepts were turned into a rigid dichotomy. That rigid dichotomy radically decreased the usefulness of the terms. “Turning things into a rigid dichotomy” is exactly what I see a lot of testers doing all the time. And the wider industry is responding by devaluing testers who they see as contributing no real operational value, except yet one more debate over terminology.

That said, yes, semantics do matter. I’ve talked about the harm of the “just semantics” dismissal before. But semantics always start as an insider (emic) perspective that has to be translated to an outsider (etic) perspective.

Another thing I want you to get out of this is that the discussion that circled around Pike’s categories followed exceptionally similar lines of argument as the discussions that now take place around the ludic and narrative ideas in games studies and, I would argue, those around testing distinctions. In the end, these discussions ended up with the effect that the terms would be jettisoned from both linguistics and anthropology because they were perceived to have no value. There are many cautionary reasons as to why that happened, which would be too long to recount here. Many ludologists and narratologists have worked hard so that the same does not happen in games studies. By which I mean there was a time where it seemed the terms “ludology” and “narratology” would be jettisoned because they were perceived to obfuscate more than clarify.

If testers truly want their distinctions to be operationally useful and culturally relevant outside of themselves — meaning they don’t want terms like, say, “test” and “check” jettisoned — then I would argue those testers have to learn from this history to make sure the same doesn’t happen in our discipline as well. I would argue this is even more so the case with Bolton’s reasoned terminology distinctions around exploratory, experiential, transformative and so on. This is too important a discussion for testers to not be having.

Having these discussions is often best done when informed by a lot of the history, such as that which I’ve tried to recount in various posts on this blog. As I’ve argued, most recently in my previously mentioned “history of automation” post, however, I’m not entirely convinced test specialists even know about much of this history such that they can draw lessons from it. That’s a large part of why I wrote my “History and Science” series and why so much of my work on this blog has been to provide a wider-angle lens around how so much intellectual history could, and should, inform testing.

The downside, of course, is that on that very point, I’ve always risked seeming quite irrelevant as I discuss a whole lot of stuff that someone could very easily argue does nothing to be operationally useful for traversing the insider/outsider divide. I’m fully well aware of this and it would be a delicious irony, for this post in particular, if that were true. Thankfully, I have some reasons for believing that isn’t entirely true but it’s certainly something that’s always on my mind with every such post.

Maintaining a Critical Distance

One focal point of Pike’s argument for his emic category — which he referred to as “knowledge of a local culture” — was an attempt to understand, in Pike’s words, “how to act without necessarily knowing how to analyze [one’s] action.” By this Pike said:

When I act, I act as an insider; but to know, in detail, how I act … I must secure help from an outside disciplinary system. To use emics of … behavior I must act like an insider; to analyze my own acts, I must look at … material as an outsider.”

This, again, is that critical distance I brought up before. I feel testers have to really put themselves in the shoes of “outsiders” and ask what those people are thinking when they hear a tester say this:

There is no such as manual testing! You don’t write a test, you perform a test! Automation cannot test, it can only check! It can work but it may not work!

Consider that in contrast to Michael Bolton’s words in his previously mentioned post:

If you want to understand important things about testing, you’ll want to consider some things that commonly get swept a carpet with the words “manual testing” repeatedly printed on it. Considering those things might require naming some aspects of testing that you haven’t named before.

I know which one hooks me more. I would further frame Michael’s thought by saying “manual testing” is one of those suitcase words I’ve talked about. It has to be unpacked. Michael’s statements are an invitation to participate and learn. What I hear from many testers, by contrast, is exhortations of how reality isn’t what you think it is. Framing matters.

Even if the outsider is willing to engage with those simple exhortative talking points, what I most often find is the testers trotting out those phrases can’t actually show what operationally changes, either in behavior or mindset, if one adopts the talking points. What most testers sound like is they are quoting someone else — which they often are — but without really knowing what to actually do with that information once it’s been stated. So an outsider might then ask things like this:

- “Okay, but how does what you just said help you work with my developers more closely to put in place better testing, particularly at the code level?”

- “How does what you just said help us get around our current problem of extremely poorly defined requirements and user stories?”

- “How exactly does what you just said translate to helping us with our significant regression problem?”

- “How does this help me with the divide we have between whether testers should do all testing or developers should do some testing? Or maybe even if developers should do all testing? Or maybe the product team should do the testing?”

You’ll also get much more specific focused responses from outsiders, like:

- “How does this help us understand the way to situate testing in our machine learning applications?”

- “How does all this help us figure out how to build automation that does maintain good test principles?”

- “How does what you are saying translate into helping us figure out better testability overall?”

On those points, I’ve tried to frame answers to those via the following:

- The tester role in machine learning series

- Design around an open source automation tool

- Ode to testability series

Was I relevant in all that? I don’t know. I hope so! Feedback suggests I wasn’t entirely irrelevant. But the point is that this wider context was required, at least in my view, to bridge the insider/outsider divides that sometimes existed between my discipline and the pressures of the industry on developers, product teams, or decision makers. They didn’t need phrases or even terminology distinctions. That wasn’t what was compromising their view of testing. What was compromising their view of testing was the lack of an extended context that showed testing with some operational specificity around what they were dealing with day to day.

So if I was writing a thesis, my conclusion might be: I believe testers are more emically-centered and simply talk to each other about their talking points. These talking points don’t translate well to a wider industry that is not as predisposed to the current group-think of testers. I think testers need to be more etically-centered and, thus, translatable to the wider industry.

Historical Matters Can Guide Us

Okay, so where are we here? Well, the emic/etic discussions were important. Or, rather, should have been.

For linguists and anthropologists more generally, however, the debate was initially important, then marginalized, and then reduced to a simple dichotomy. Either one was an “insider” — a person born to a culture and language tradition — or one was an “outsider” — a person trying to understand from the outside what the language and culture were all about.

For two or three generations, students in both fields were taught of the emic and etic as opposing perspectives. An anthropological linguist named Dell Hymes noted that: “much of their popularity [as terms], has indeed been due to their being assimilated to a dichotomy.” If curious, you can check out Hymes’ essay “Emics, Etics, and Openess: An Ecumenical Approach” in the previously referenced Emics and Etics: The Insider/Outsider Debate. The upshot is that the discussions were not had or, rather, were had in very simplified, non-extended forms. Thus the discussions were ultimately deemed to lack utility, and thus value, and so, because of that, the concepts and terms of the discussions were easily reduced to simplified terms, and then marginalized, and now largely forgotten.

Yikes! So, wait, didn’t all that hurt the discipline a bit? Didn’t the practitioners who engaged in all this “useless” discussion suffer some serious blowback? No, not really. Yet I argue the opposite will, or at least can, happen for testers and I’ve already seen plenty of evidence of that happening. In fact, so have testers. They too see an industry devaluing testers (as skilled practitioners of a discipline) and testing (as a specialized discipline). They simply ascribe different reasons for that devaluating than I do, as I stated earlier.

But, hold on, why is is that all this didn’t hurt linguistics/anthropology but may hurt testing? Well, both linguistics and anthropology had centuries of disciplinary, and cross-disciplinary, history to sustain them when this particular discussion evaporated. Testing, at least in the software and hardware context, does not have that kind of institutional bedrock to rest on.

In the game studies context I mentioned, each scholar in game studies have learned to use the perspective of the ludic to uncover further meaning of the narrative, or the opposite and use the story to elucidate the significance of the mechanics of gameplay. Thus did the insiders and the outsiders learn to talk in a way that was comprehensible and relevant to each. But that almost didn’t happen. Such studies around “ludic” and “narrative” almost suffered the same fate as “emic” and “etic” in linguistics and anthropology.

And that would have been a problem because game studies, at least in terms of digital games, is a similarly very young field much like technology-focused testing. Hymes put it this way:

When the issues of “emic” and “etic” are treated as passé, they appear to me to treat the craft of anthropology [and linguistics] as passé …. Let me conclude by saying that these matters are not matters of anthropology and linguistics alone …. The craft of linguistic ethnography, of patient attention and discovery, of teasing out of pattern, of willingness to watch, listen, and be surprised, expressed a respect for local knowledge and local systems … and it must respect the narrative structures of others, the speech act constellations of others, the historically, experientially derived values and norms of others.

That comes from the same essay I mentioned previously. What Hymes hoped to offer the emic/etic debate in anthropology and linguistics is something that Matthew Kapell, Johansen Quijano, and Amy Green, as well as many others, have attempted to do in digital games studies. It’s something I’ve hoped to do in the testing arena and what I certainly feel practitioners like Michael Bolton hope to do as well. I certainly don’t want the craft of testing in a technology context to ever become passé.

With all this, of course, it could be argued that Pikes, Harris and Hymes, failed. The discussion essentially withered on the vine. In fact, an anthropologist named Marshall Sahlins described the outcome for his discipline distinctly, noting that:

[Anthropologists] have become the working-class of the Cultural Studies movement … relegated to the status of ethnographic proles in the academic division of labor.

That comes from Sahlins’ book Waiting for Foucault, Still published in 2002. Read “proles” as a worker or a member of the blue-collar working class. Someone employed at a mill or a factory was considered a prole. Shades of perhaps “manual labor” there? Could se take Sahlins’ statement and rephrase it as a concern:

“Testers have become the working-class of the hardware and software industry … relegated to the status of technological proles in the division of labor.”

I certainly hope not. And, again, I’ll point out that there was a danger that games studies scholars would occupy a similar position in the larger world of digital media studies. As Matthew Kapell said in The Play Versus Story Divide when he saw that concern on the horizon:

Without a more thorough and ongoing debate among practitioners the one major paradigmatic argument that has fueled the emergence of the field may evaporate as the emic and etic debate did only a generation ago in anthropology and linguistics. And, without some debate to hang on to there will be little for scholars in other fields (our own outsiders) to see when they stop by to understand exactly what it is that digital game scholars are doing. They will find only chaos when they visit. If that happens we will only be talking to ourselves.

Exactly! Talking to ourselves.

That is entirely what I think a broad industry of testers have done and are doing. They have solidified around certain talking points that they reinforce to each other, convincing themselves ever more, but while doing little to nothing to convince a wider industry. It’s the very definition of a self-imposed echo chamber where group-think stands a good chance of settling in and where so-called “cults of personality” start to emerge. And, as history has shown us, most “culture wars” tend to be fought around certain cults of personality.

Now, again, you might say: “Well, how bad can it be? After all, anthropology and linguistics still exist even after all that.” But, again, each of those disciplines had long histories behind them, and significant institutional momentum. Testing, in our context, does not. Well, it actually does but it doesn’t get treated that way. Testing itself has a very long pedigree. See my post on The Testing Pedigree. But in a technology context like the one most of us are dealing with, it does not.

Discussions around testing, right now and, I would argue, since about 2009 or so, have proceeded in far too combative of a process, wherein relatively few people are trying to control the narrative. That usually happens when people believe they are in a “cultural war” as I mentioned at the start of this post. I’ve tried to show one concern of that in how we didn’t resist the lull of automation. I’ve tried to show that in how we haven’t really fought orthodoxy very well. I’ll turn to Kapell again here on his thoughts on game studies:

Mature fields of inquiry … welcome competing ideas and work to further their paradigms. Mature disciplines also eventually agree on central themes based on the ideas presented, not the individuals presenting them. It is, frankly, time for game studies to grow up.

Exactly that. That pretty much mirrors what I said in my pedigree post:

Our discipline has an incredibly rich pedigree that can inform us. Let’s start acting like it.

And what I hope I’ve clarified in this post is that “acting like it” means, in part, finding a way for the emic to resonate with the etic; for the view of the insiders to foster comprehension and promote relevance among the outsiders.

If we do that, perhaps we won’t really have to worry so much about who is an insider or an outsider.

That feels like a nice world to live in.